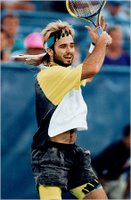

Stage Left, Sage Right: Agassi Says Goodbye

by Karen Crouse, NY Times

The day that Andre Agassi has had circled in his mind for months is almost here.

It is not the opening day of the United States Open, where his first-round match against Andrei Pavel will cue a royal reception. That Agassi will suffer gratefully.

The day he has been looking forward to will dawn after his last match of the tournament, whether it is the first round or the final. Because only when Agassi retires from competitive tennis will he be free to shift attention off himself for good.

“This is a close of a certain chapter of my life, you can’t deny that,” Agassi said recently over a cheese omelet lunch in Las Vegas, his hometown. What comes after his retirement, “is the birth of who I’ll continue to strive to become.”

There is a notion, propagated by many former elite athletes, that retirement is a kind of death. Agassi scoffs at that. “I was 141st in the world,” he said, remembering his ranking in November 1997. “That felt like death.”

Can life after tennis be as stimulating? Pete Sampras, Agassi’s chief rival on the court in the 1990’s and his polar opposite off it, left competitive tennis shortly after winning the 2002 United States Open, only to resurface this summer playing World TeamTennis because he was bored. “There’s no book on retirement,” Sampras said.

It would be just like Agassi to write one. He refuses to look at retirement as a territory as desolate as a moonscape. “It’s an environment I plan on thriving in,” he said.

After everything that he has crammed into his first 36 years — including eight Grand Slam titles, $31 million in prize money, two marriages and two children — who would doubt him?

“In his life after tennis he will accomplish more than what he did playing tennis,” said Patrick McEnroe, the United States Davis Cup captain who lost all four of his matches against Agassi as a player. “It sounds outlandish, but I feel comfortable saying that.”

Agassi’s ace in the hole, as he calls it, is this: While fashioning a Hall of Fame résumé on the court, he has built a rich, full life away from it. The evidence of that, friends say, is everywhere in the house 15 miles west of the Las Vegas Strip where Agassi lives with his wife, Steffi Graf, and their two children, Jaden Gil, 4, and Jaz Elle, 2. There is not a tennis trophy or tournament memento in sight, nothing at all to indicate that a couple with 30 Grand Slam singles titles between them resides there.

People are on display instead, friends and family captured in dozens of professional-quality photographs taken by Graf. The focus of Agassi’s future will be the people in those pictures. “I’m really clear about this being the right time to retire,” said Agassi, who turned pro at 16. “I want to be around the people in my life I enjoy.”

“What he needs is the connection,” said Perry Rogers, Agassi’s best friend. “He can’t function without it.” Agassi met Rogers, when Rogers was 12 and Agassi 11. His trainer, Gil Reyes, has been with him for 17 years, commanding and cajoling Agassi to be self-centered. Theirs is the only relationship that Agassi abides in which the focus is firmly on him. “My job has been to get him to be as good to himself as he is to others,” Reyes said in a telephone interview. Reyes is the one who pushes him to rest, eat and prepare. Agassi’s bedrock relationship, though, is with Graf, whom he married in October 2001 after a two-year courtship that was preceded by many years of infatuation on his part.

Graf turned pro at 13, and at 19 became the fifth player to win all four Grand Slam singles titles in the same year. She won 107 singles titles and $21 million in her 17-year career. On the face of it, theirs looked like a star-crossed love match, this woman known for her cool, unemotional presence linked with a man who was his own worst opponent. They had their first date in the summer of 1999, after Agassi’s two-year marriage to the actress Brooke Shields ended and as Graf’s Hall of Fame career was winding down. It did not take long for them to find common ground beyond the tennis court.

“Two minutes around her and you forget what she’s done in tennis,” Agassi said of Graf. They seem to live at the same frequency, their antennae picking up other people’s faintest wants and needs. After spending half their lives on the professional tennis circuit, where socializing among players has largely gone the way of the serve-and-volley game, Agassi and Graf seem eager to make up for lost soirees.

They entertain often. Among friends, they are famous for memorizing everybody’s orders when they are dining out, then reproducing the same dishes and drinks when they have those friends over to their home. “We’re not settled unless everyone around us is settled,” Agassi said.

As far back as the junior circuit, Agassi was adamant about wanting to lead a rich life even if it cost him tennis titles. He still managed to win all four majors, completing his career Grand Slam at the 1999 French Open with a five-set victory against Andrei Medvedev. Tennis never ruled Graf, either, even when she was dominating it. That much was made comically clear during a tournament a few years back. While playing a trivia game online to pass the time before a match, Agassi came upon a question he was sure he would ace: “Who is the only woman to win a Grand Slam final 6-0, 6-0?” The choices were Graf, Helen Wills Moody, Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova.

Agassi turned to Graf, who was in the room, and asked, “Did you ever win a Grand Slam final love and love?” She answered, “No, I don’t think so.” Agassi picked Moody, but the answer was Graf, who beat Natasha Zvereva at the 1988 French Open. Agassi turned to her and said, “How could you not remember that?” Her answer was telling. She said she did not commit the details to memory because she never wanted tennis to matter that much.

“That’s why those two are perfect for each other,” Rogers said.

On this day in early August, the body of the player who used to wear diamond stud earrings and gold ropes is unadorned save for a necklace made by his son with square beads that spell out “Daddy Rocks.” Parenthood has transformed Agassi’s life. “I don’t remember what I used to do with my time or what used to preoccupy my thoughts,” he said.

That is the chief seduction of retirement. He never again will have to put his tennis ahead of his children. It weighs on him when Jaden tugs at his shorts and says, “Daddy, race me!” and Agassi has to say, “Not today, son. I’ve got to play tonight.”

Agassi has changed over the years, although not as conspicuously as it seemed. He was never as one-dimensional as his teenage James Dean persona. Playing a rebel made Agassi rich, but it did not make him happy. In the early 1990’s, he split with his image makers from the major sports agency, International Management Group, and retained his best friend, Rogers, to oversee his business affairs.

It was a decision that many people saw as a recipe for ruin. Even Rogers wondered if it was prudent to mix finances with friendship. But Agassi’s argument was persuasive. “They don’t know me like you do,” he said.

In 1993, Rogers, who has a law degree from Arizona, was named president of Andre Agassi Enterprises, a company Agassi founded because he wanted to make money and make a difference.

On the business side, he successfully invested in a restaurant owned by a friend, the chef Michael Mina, and the partnership has grown to eight restaurants. Agassi and Rogers were among five longtime friends who bought the Golden Nugget hotel on the Strip for an initial cash investment of $50 million. They sold it less than two years later, receiving $163 million in cash, according to documents filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Agassi’s greater passion is the charitable arm of his foundation. Its stated goals are to assist underprivileged, abused and abandoned children in southern Nevada. One of the first recipients of the foundations largesse was a Boys & Girls Club in the poorest part of Las Vegas.

When Agassi’s game went Hollywood in 1997, after he married Shields and moved to Los Angeles, Rogers worried that the charity’s fund-raising might suffer. Then came Agassi’s victory at the French Open, which he followed with his second United States Open title, to finish 1999 ranked No. 1, the first and only year in which he did so. After raising his game from the dead, raising money and people’s consciousness would no longer be a concern. Agassi was back in the spotlight, only this time he had figured out how to use it to benefit others. “The French Open changed everything,” Rogers said.

In 2001 the Andre Agassi College Preparatory Academy opened, around the corner from the Boys & Girls Club, with third grade through fifth grade. The public school, constructed and financed by tax dollars and Agassi’s foundation, now extends from kindergarten through 10th grade. Classrooms for the 11th and 12th grades are under construction.

He and Rogers contributed $2.5 million to the school last year as part of a fund-raising gala for children’s programs that brought in $10 million and included a surprise performance by Barbra Streisand. The foundation and its offshoots also contribute to dozens of health and education programs for at-risk children, including financing college scholarships, grants for disadvantaged children to attend camps and programs that work to prevent domestic violence against women and children. One of the recent projects provides shelter for children who have been removed from dangerous home situations or whose parents cannot care for them and includes 24-hour health care and a school.

It is on these programs that Agassi plans to devote considerable time after he takes one last walk to the net. Tennis is a sport that lets a player touch the lives of his audience for a few hours, he said over lunch, adding, “When you touch a person’s life outside the lines, it has more permanence to it.”

On this afternoon in Las Vegas, Agassi had a full plate of commitments. But he is in a hurry only to begin his next act.

“I feel like I’ve been practicing 20 years for this,” he said.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home